“Your body sends four times as much information to your brain as your brain is sending to your body.”

Read on or listen here:

If you’ve been following along with the stress reset series this week, you’ve stopped scrolling, taken some deep breaths, dunked your face in cold water, looked at something green and growing. Maybe you’ve noticed small shifts – a moment of calm, a slightly slower heart rate, a sense of coming back to yourself even briefly.

But have you wondered why these simple actions work? What’s actually happening in your body when you sigh deeply three times, or splash cold water on your face, or step outside into greenery?

The answer lies in understanding one of the most important parts of your nervous system – your vagus nerve. And once you understand how it works, you gain access to the master switch for your own stress response.

The Wandering Nerve

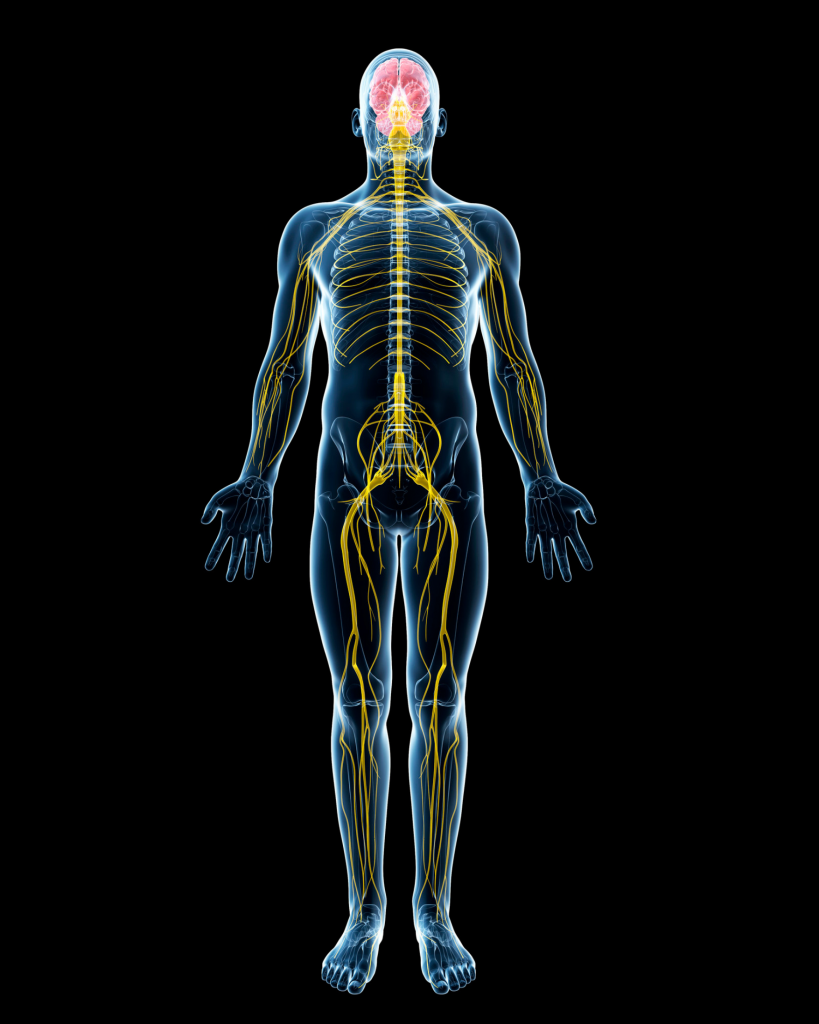

The vagus nerve gets its name from the Latin word for “wandering,” and wander it does. This remarkable cranial nerve originates in your brainstem and meanders through your body like a river system, touching your heart, lungs, digestive tract, and most of your major organs along the way. It’s the longest nerve in your autonomic nervous system, and it’s essentially the biological highway connecting your brain to your body.

Think of your vagus nerve as the main cable in your body’s communication network. When it’s functioning well, messages flow smoothly between your brain and organs. Your heart knows when to speed up and slow down. Your digestion works efficiently. Your immune system responds appropriately. Your breathing deepens naturally. You can shift from alertness to rest with ease.

When vagal function is impaired – what researchers call “low vagal tone” – everything becomes harder. Your body stays stuck in high alert even when there’s no real threat. Anxiety feels like a constant companion. Sleep becomes elusive. Digestion goes haywire. Recovery from stress takes longer.

This is why understanding your vagus nerve matters. Because unlike many aspects of your nervous system that operate entirely outside conscious control (although more on that now contentious point later!), you can actually influence vagal function. You have tools. You have agency.

The Two Branches of Your Nervous System

To understand how the vagus nerve works, we need to step back and look at the bigger picture of your autonomic nervous system – the part that runs automatically in the background, keeping you alive without requiring conscious thought.

Your autonomic nervous system has two main branches:

The sympathetic nervous system – your accelerator pedal. This is your “fight or flight” response, designed to mobilise energy quickly when you face danger. Heart rate increases, breathing quickens, blood flows to your muscles, digestion shuts down. Brilliant for escaping actual threats. Exhausting when activated constantly by modern stressors like emails, deadlines, and social media.

The parasympathetic nervous system – your brake pedal. This is your “rest and digest” response, responsible for recovery, healing, digestion, and all the maintenance work your body needs to do when you’re safe. Heart rate slows, breathing deepens, digestion activates, inflammation reduces.

Your vagus nerve is the primary component of your parasympathetic nervous system. It’s the brake pedal. The calm-down signal. The “you’re safe now” message that allows your body to shift from survival mode into recovery mode.

Here’s the problem: most of us in modern life are driving around with our foot constantly on the accelerator and a malfunctioning brake. We’re activating our sympathetic nervous system all day long – stress, screens, caffeine, rushing, worry – but we’re not giving our parasympathetic system enough opportunity to do its job. Our vagus nerve becomes underactive. We lose the ability to downregulate effectively.

The result? Chronic stress that our bodies can’t resolve. Anxiety that won’t shift. Sleep that doesn’t refresh. Digestion that’s perpetually disturbed. A nervous system stuck in a state that was only ever meant to be temporary.

Measuring Vagal Tone

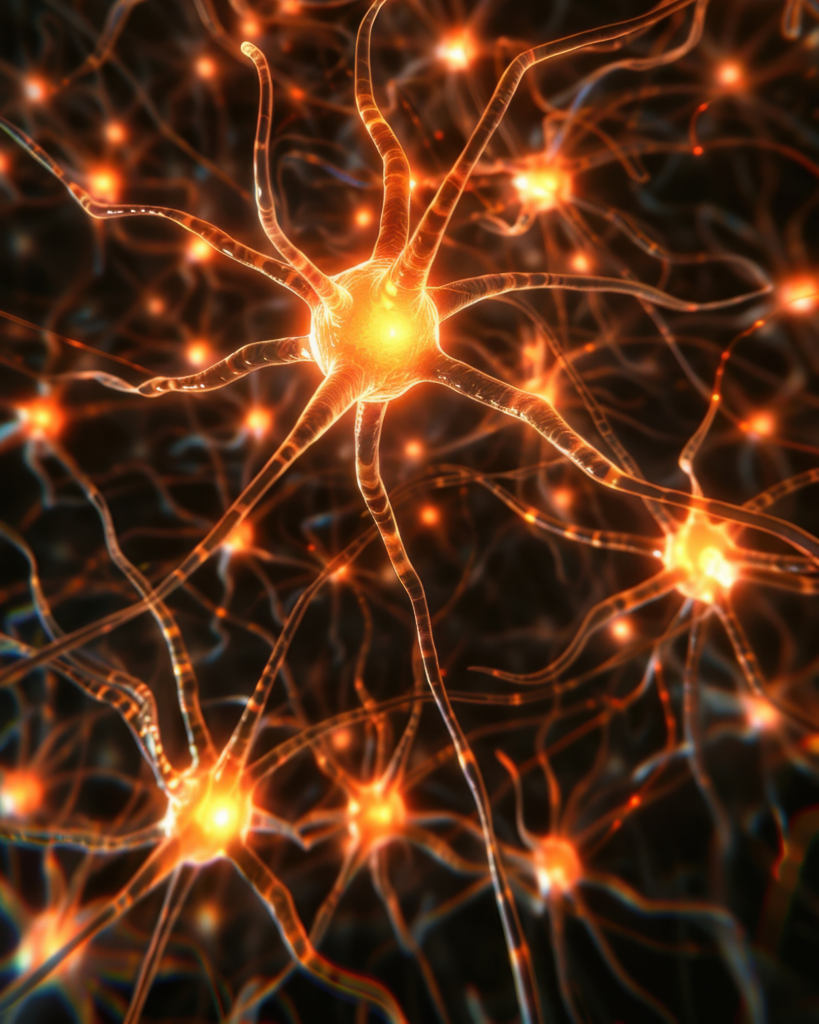

Scientists can actually measure how well your vagus nerve is functioning through something called heart rate variability, or HRV. This measures the variation in time between your heartbeats, and it’s one of the most reliable indicators of overall health and stress resilience.

You might think a perfectly regular heartbeat would be ideal, but the opposite is true. A healthy heart rate should show variation – speeding up slightly on the inhale, slowing down on the exhale. This subtle dance indicates that your vagus nerve is actively engaged, constantly fine-tuning your heart rate in response to what your body needs.

High HRV means your vagus nerve is responsive and flexible. You can shift between states easily. You recover quickly from stress. Your body has room to adapt.

Low HRV suggests a vagus nerve that’s sluggish or overwhelmed. You stay activated longer after stress. You struggle to transition from work mode to rest mode. Recovery takes longer. Everything feels harder than it should.

The beautiful thing? HRV isn’t fixed. Vagal tone can be improved through specific practices. You can literally train your nervous system to respond more flexibly to stress. This is what the past week of simple interventions has been doing – strengthening your vagal tone through repeated, gentle activation of your parasympathetic nervous system

Why Those Simple Practices Work

Now we can understand why those “stop scrolling” interventions actually work. They’re all vagal stimulators – direct ways to activate your parasympathetic nervous system and tell your body it’s safe to stand down from high alert.

Deep breathing, especially with extended exhales: Slow, diaphragmatic breathing directly stimulates your vagus nerve through mechanoreceptors in your lungs and diaphragm. When you lengthen your exhale, you’re sending a powerful “calm down” signal. The research is clear – just three physiological sighs (deep inhale, second inhale, long exhale through the mouth) rapidly reduce autonomic arousal and stress.

Cold water on your face: This triggers something called the “mammalian dive reflex.” When cold water hits your face, your body thinks you’re diving underwater and activates an ancient survival response that immediately slows your heart rate and shifts your nervous system toward parasympathetic dominance. It’s not comfortable, but it works faster than almost anything else for acute anxiety.

Looking at greenery and nature: Natural environments provide what researchers call “soft fascination” – gentle sensory input that captures attention without demanding focus. This allows your prefrontal cortex (the thinking, worrying part of your brain) to rest whilst your sensory systems engage with something soothing. Green spaces consistently reduce cortisol and increase vagal tone.

Gentle movement and stretching: Yoga, walking, slow movement – these all stimulate vagal pathways through proprioception (awareness of your body in space). They shift attention from mental rumination into physical sensation, which naturally activates parasympathetic response.

Humming, singing, or chanting: Your vagus nerve passes through your vocal cords. Vibration in your throat from humming or singing directly stimulates it. This is why singing feels good, why chanting has been used in spiritual practices for millennia, why humming can rapidly shift your state.

These aren’t random folk remedies or wellness trends. They’re direct, biological interventions targeting your vagus nerve and parasympathetic nervous system. Understanding the mechanism doesn’t make them work better, but it does help you trust them enough to actually use them when stress hits.

Living Wild, Recovering Well

During my year living entirely in the wild, I had no choice but to develop intimate familiarity with my nervous system. Cold water immersion wasn’t optional – it was how I bathed. Deep breathing wasn’t a practice – it was survival when fear arose in the dark. Contact with nature wasn’t therapy – it was constant, unavoidable immersion.

What I discovered through necessity, research is now confirming: these practices fundamentally reshape how your nervous system responds to stress. I didn’t have lower stress in the wilderness – if anything, I faced more genuine challenges daily than I do now. But my capacity to regulate that stress, to shift from activation back to calm, became remarkably efficient.

My vagal tone strengthened not through any single dramatic intervention but through thousands of small moments of asking my nervous system to flex, to adapt, to shift states. Cold water every morning. Deep breathing in uncertain moments. Constant sensory engagement with the natural world. Movement as necessity rather than exercise.

The practices I teach now through Feral Therapy aren’t asking you to live in the woods for a year. They’re offering the concentrated essence of what that experience taught me – ways to strengthen your vagal tone and nervous system flexibility within the context of modern life.

Beyond Survival Mode

Here’s what really matters: when your vagal tone is strong, you don’t just cope better with stress – you transform your relationship with it entirely.

Instead of anxiety that persists for hours after a stressful event, you feel activation and then recovery. Instead of lying awake at night with your mind racing, you can consciously shift into parasympathetic dominance. Instead of snapping at loved ones because your nervous system is overwhelmed, you maintain capacity for patience and connection even when challenged.

You develop what researchers call “stress resilience” – not the absence of stress, but the ability to meet it, respond appropriately, and return to baseline quickly. You build capacity not just to survive difficult periods, but to move through them with something approaching grace.

This is particularly relevant if you’ve been through what I’ve been through recently – difficult October, significant stress, experiences that leave your nervous system humming with residual activation. Understanding your vagus nerve gives you specific, concrete tools for supporting your own recovery.

You’re not at the mercy of your stress response. You have the brake pedal. You just need to remember to use it.

Practical Nervous System Support

So how do you strengthen vagal tone and support parasympathetic function in daily life? Here are the practices I return to again and again, for myself and with clients:

Morning breathing practice: Before you even leave bed, spend five minutes with slow, deep breathing. Four counts in through your nose, hold briefly, six to eight counts out through your mouth. This sets your nervous system’s baseline for the day.

Cold exposure: Even thirty seconds of cold water at the end of your shower provides measurable vagal stimulation. Build gradually. The discomfort is the point – you’re training your nervous system to handle activation and recover quickly.

Regular nature contact: Daily if possible, even briefly. Garden, park, trees visible from your window. Your nervous system needs regular contact with natural environments to function optimally.

Humming or singing: While cooking, driving, whenever. The vibration stimulates your vagus nerve directly. If you feel self-conscious, do it in the shower.

Gentle movement: Walking, stretching, yoga. Not intense exercise that activates your sympathetic system, but movement that keeps you present in your body.

Social connection: Genuine connection with safe people activates your social engagement system, which is mediated by your vagus nerve. This is why isolation makes everything worse and connection makes everything more bearable.

Meditation and stillness: Simply sitting, noticing, being present. This might be the hardest practice of all, but it’s also one of the most powerful for developing nervous system flexibility.

The key is consistency rather than intensity. Small, regular practices reshape your nervous system more effectively than occasional dramatic interventions. You’re not trying to fix yourself – you’re training a biological system to function more flexibly.

The Bigger Picture

Understanding your vagus nerve and nervous system regulation is about more than just stress management. It’s about reclaiming agency over your own biological responses. It’s about recognizing that you’re not broken when stress affects you – you’re human, with a nervous system doing exactly what it evolved to do.

But you’re also not helpless. Between the stimulus of stress and your response to it, there is space. In that space lives your vagus nerve, your breath, your capacity to consciously engage your parasympathetic system and tell your body it’s safe to stand down.

The interventions we’ve explored this week aren’t just coping strategies – they’re ways of befriending your own nervous system. Of learning its language. Of developing the literacy to read your own stress signals and respond with appropriate support rather than more stress.

This is the deeper work of the stress reset. Not just getting through difficult periods, but emerging from them with a stronger, more responsive nervous system. Not just surviving, but building genuine resilience – the kind that comes from understanding how your body works and giving it what it needs.

Your vagus nerve is wandering through your body right now, connecting brain to heart to gut to every major system. It’s waiting for signals of safety, for cues that it’s okay to shift from survival mode into recovery. You can send those signals. You have the tools.

The question is: will you use them?

Are you curious about developing a deeper relationship with your nervous system through nature-based practices? Whether you’re drawn to cold water therapy, breathwork, meditation, or simply learning to slow down in natural environments, these practices can transform how you experience and recover from stress. Reach out if you’d like to explore what nervous system support might look like for you.

Follow the stress reset series on social media for daily practices, or subscribe to receive monthly insights on nature therapy, resilience, and living well. Your nervous system will thank you.

No responses yet